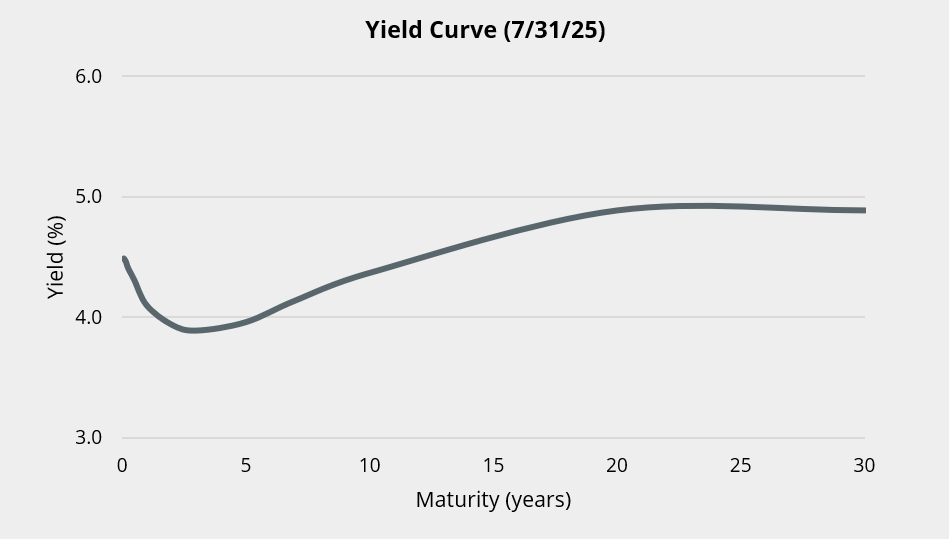

Why Fed cuts may not benefit the entirety of the yield curve.

We’ve written extensively about our concern that the credit markets are underpricing risk. We measure this by looking at the additional yield, referred to as the “spread”, an investor picks up by moving from an ultra-safe U.S. Treasury bond to a similar maturity corporate or other non-Treasury bond. Today, most of these spreads are at or near historically tight levels, providing little excess reward for taking on credit risk.

What about interest rate risk?

The other primary risk fixed income investors face is interest rate risk. Most of us know that rising interest rates will negatively impact the price of a bond, while falling rates generally result in gains. The longer the maturity of the bond, the more the price will move, up or down, for a given change in yield.

When describing the level of interest rates, we generally refer to the yield-to-maturity on U.S. Treasury securities. We start with the 3-month T-Bill and go out to the 30-year Treasury Note, plotting everything in between to create the yield curve. Why Treasuries? Because historically, they have been considered the safest, most liquid security in the world. Everything else has inherently more risk and is measured against Treasuries.

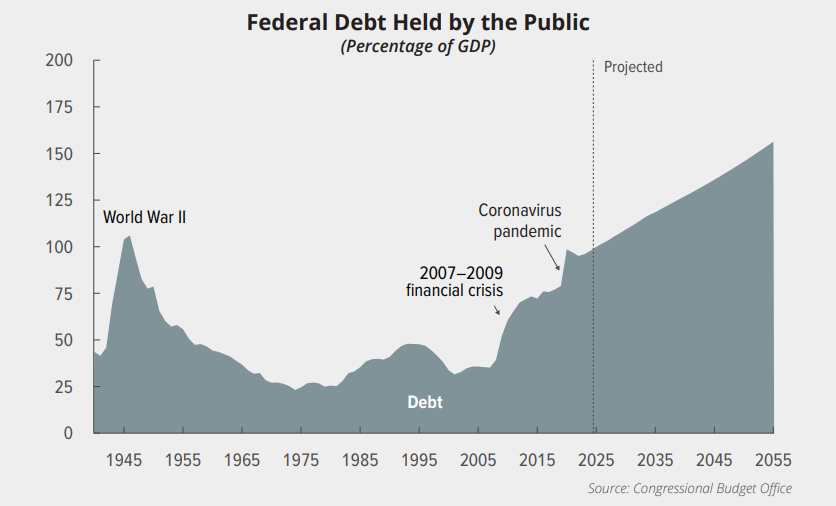

What if U.S. Treasuries are no longer considered riskless?

Deficit spending, in good economic times and bad, has put the U.S. fiscal outlook on an unsustainable path. In less than 20 years following the 2007 Financial Crisis, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio has nearly doubled from 60% to over 120%. The Congressional Budget Office’s most recent long-term projections forecast that it will reach 156% over the next 30 years, and that seems optimistic should the indifference to address the deficit continue.

The Risk – Higher Term Premiums

The Treasury term premium is defined as the additional compensation that investors require to hold long-term government debt rather than simply continuing to invest in short-term debt. Historically, that was largely based on the market’s expectation for the future path of short-term Treasury yields. But fiscal uncertainty and concerns about the U.S.’s ability to service its debt may force investors to demand additional yield to hold U.S. Government debt.

In fact, most economists believe the markets are already building in a higher term premium, and it could get worse, regardless of the policy rate.

Why does it matter?

U.S. Treasuries are not just used to price fixed income securities. They are, directly or indirectly, the basis for valuing just about every other asset class in the world. Investors use Treasury yields as the base discount factor in valuing fixed income securities, equities, commodities, futures, options, real estate – you name it. They set the base for commercial loans, residential mortgages, credit card debt, and nearly every other form of credit. The U.S. Dollar is the world’s reserve currency; its stability is central to international trade and economic growth both here and abroad. Higher term premiums will almost certainly reduce the value of assets and act as a drag on economic growth.

Summary

Historically, investors took the stability and liquidity of the U.S. Treasury market for granted. Decades of deficit spending have put the U.S. on an unsustainable fiscal path. Absent reduced spending or an increase in taxes, a higher term premium on longer-dated Treasuries would reverberate across markets, reshaping asset valuations, borrowing costs, and measures of economic performance.